Dance in Finland has always been international. This internationalism has meant training and making a living, artistic collaborations of many kinds, and an opportunity to compare the quality of one’s work in international competitions. Dance scholar Aino Kukkonen ponders how these international contacts were born, how have they have served as inspiration, and what they have produced over time in her article on the flow of influences between Finland and other countries in the field of dance.

Where did it all begin?

The field of professional dance as an art form began to take shape in Finland in the first decades of the 20th century. Finland didn’t have a tradition of a court ballet; ballet and modern dance at that time were developing in tandem. The first production of what is now the National Ballet was a performance of Swan Lake one hundred years ago, in January of 1922.

Maggie Gripenberg’s work (1881-1976) was among the first that allowed Finnish audiences to see modern dance as an art form. Her career was an interesting example of the work of the international woman artist. Gripenberg was born to an aristocratic family supportive of music and other artistic endeavors. She was on her way to becoming a visual artist but the direction of her life changed decisively when she took a long study trip to Dresden in 1904 and saw Isadora Duncan perform. Maggie began studying dance under the guidance of a pupil of Duncan’s in Sweden and continued her studies in Germany and later in England.

Gripenberg worked as a dancer and choreographer at the Finnish National Theatre and the Finnish Opera and also created original works for her advanced pupils. In the 1910’s she actively performed abroad as well, in the Baltic countries, England, the United States and elsewhere, which was not uncommon among professional dancers of the time. Gripenberg’s group won a gold medal at an international dance competition in Brussels, and her career as a dance pedagogue spanned more than 40 years.

In the 1920’s many Finnish dancers had close connections with Central Europe and the influential trends in modern dance there. The Finnish artist Ester Naparstok, for example, danced with Rudolf Laban’s group in the 20’s. Key international names of the day also visited Finland. Though the Second World War interrupted dancers’ contacts with other countries, after the war Finns successfully participated in Nordic dance competitions.

The dynamic 60’s

In the first half of the 20th century the movement known as free dance didn’t have an established status or regular venues like ballet or professional theater did. To remedy shortcomings in training, the Union of Finnish Dance Artists began bringing foreign dance instructors to Finland in the 1950’s. The first course in Graham technique was offered in 1958.

In the 1960’s, audiences were treated to appearances by top dance groups. Finland was visited by the Martha Graham Company in 1962, Merce Cunningham Dance Company in 1964, Alvin Ailey American Dance Theater in 1965, and Donald McKayle’s Black New World in 1967. These visits also influenced future modern dance professionals’ experience of what dance could be.

One particular messenger of American modern dance in Finland was Riitta Vainio (1936–2015). After graduating as a physical education teacher, Vainio received her dance training at the beginning of the 1960’s at the Philadelphia Dance Academy. When she returned to Finland in 1961, the dynamic Vainio began performing and teaching modern dance.

Visiting instructors at her private dance school included her colleague Dyane Gray and their teacher Nadia Chilkovsky from Philadelphia in 1963-64. The school was also visited in the 1960’s by such dancers as Ted Shorter, Cora Cahan, Norman Walker, Morris Lee Donaldson, Mary Barnett and Talley Beatty. Many also performed and created choreography for Vainio’s group.

Vainio’s work changed direction at the end of the 60’s when she started creating interdisciplinary productions and improvisations. In the 1970’s she became interested in dance therapy as well as liturgical dance, reflecting the spirit of the time. Dance was opening up for ordinary people.

Paris, Amsterdam, Tokyo

In the 1960’s and 70’s, Finnish professional dancers trained in Stockholm, Paris, Cologne, and London. New York was naturally also an important city, where such studios as Merce Cunningham’s and Martha Graham’s beckoned.

Amsterdam became an important place for young artists like Liisa Pentti and Sanna Kekäläinen in the 1980’s. At the modern dance department of the theater school there (later called The School for New Dance Development), new kinds of thinking were being developed, influenced by such things as American postmodern dance and gentle body awareness techniques. New Dance works of embodied politics and the body-mind relationship got a home when five Finnish women (among them Kekäläinen and Kirsi Monni) founded Zodiak Presents in 1986 as a production collective for independent choreographers. New Dance artists were interested in the dance process itself and broke theatrical and aesthetic norms in their works. Many also worked in performance art groups at the time. In the 1990’s, Zodiak became Zodiak – Center for New Dance.

The Japanese butoh aesthetic, its primitivity and intimate, fundamental questioning was a particular influence on Finnish contemporary dance in the 1980’s and 90’s when artists such as Kazuo Ohno, Charlotta Ikeda and Sankai Juku visited Finland. Anzu Furukawa was a visiting choreographer with Helsinki City Theatre’s dance group. Numerous Finnish choreographers such as Tero Saarinen and Arja Raatikainen have gone to Asia to familiarize themselves with butoh and other Asian dance cultures and melded elements of them into their own work.

Finnish dance groups begin performing internationally

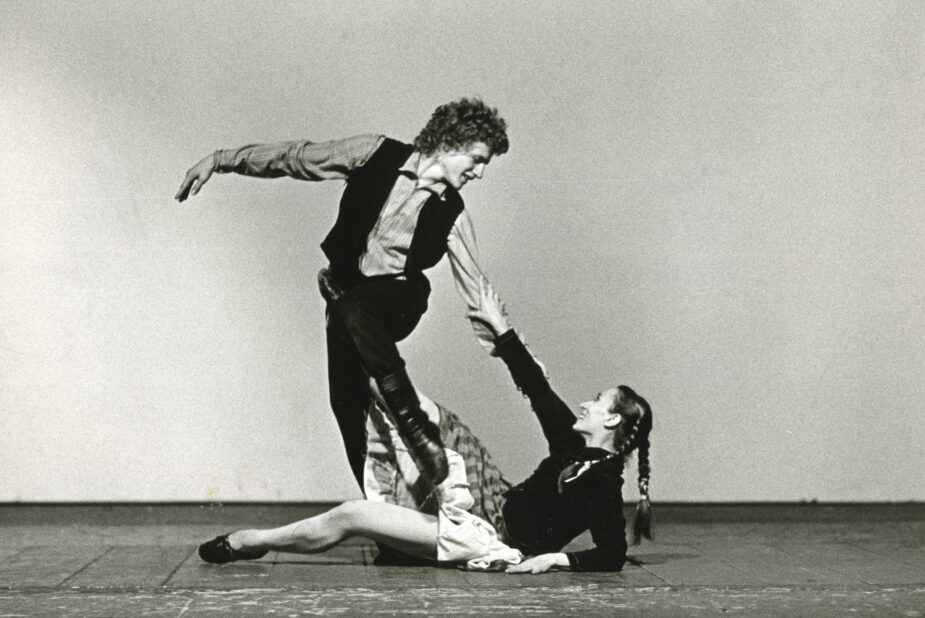

Beginning in the 1970’s, Finnish dance groups gradually started to make appearances at theaters and international festivals abroad. Works by Dance Theater Raatikko, founded by Marjo Kuusela and Maria Wolska in 1972, combined a variety of styles, and what was most important to them was what dance can say about society. Kuusela’s choreography was influenced by Kurt Jooss‘s dramaturgical ideas and work by artists such as Donald McKayle and Alvin Ailey. From its beginnings Raatikko has actively performed abroad. In addition to the Nordic countries, they have appeared in France, East and West Germany, Switzerland, Spain, Bulgaria, the Soviet Union, the United States, and elsewhere.

Another key modern dance group established in the 70’s was the Helsinki City Theater Dance Group (now known as the Helsinki Dance Company). It’s international touring began with Jorma Uotinen‘s tenure as group leader in the 1980’s. Uotinen’s ambiguous, visual dance theater received an enthusiastic reception. His 1985 piece Kalevala, based on the Finnish national epic Kalevala, was a bold major work that was presented abroad for roughly five years. Other Uotinen’s pieces such as Huuto (Scream, 1984) and Ballet Pathetique (1989) moved audiences in Europe. Ballet Pathetique has lived on not only at the Finnish National Ballet but also in the programs of seven dance groups abroad into the 2000’s.

Carolyn Carlson and Finland

The work of Carolyn Carlson, who has Finnish heritage, has been of crucial importance to Finnish dance. Carlson’s and Jorma Uotinen’s collaboration began in 1976 when Carlson was a visiting choreographer at the Finnish National Ballet and asked Uotinen to join her experimental modern dance group at the Paris Opera. Uotinen embraced Carlson’s central concepts of time, space, form, and movement in his own work. It was through Carlson that Alwin Nikolais‘s legacy of modern dance was later seen when Uotinen joined the Helsinki City Theater. Carlson’s collaborator Claude Naville‘s arrival in Finland to work with Uotinen was an important influence on Finnish lighting design.

In the early 1990’s, Carlson led the Helsinki City Theater Dance Group. The pieces Kuka vei elokuun (Who Took August) and Syyskuu (September) were performed on the group’s extensive tour of Europe. Carlson has also been a visiting choreographer at the National Ballet, Aurinkobaletti, and Raatikko.

Tero Saarinen’s breakthrough as a dancer happened when he won the gold medal at the Paris International Dance Competition in 1988 with B12, choreographed by Uotinen. Saarinen had in a sense already been in contact with Carlson’s dance philosophy when he danced in Uotinen’s pieces. In the 1990’s their paths converged when Saarinen worked in France in pieces by Carlson and others. Carlson created new solos for him, particularly Blue Lady (Revisited) in 2008. In that piece, Saarinen was able to create his own interpretation of Carlson’s legendary 1983 solo. Each found in the other an inspiring kindred spirit.

The slipstream of Finnish contemporary dance

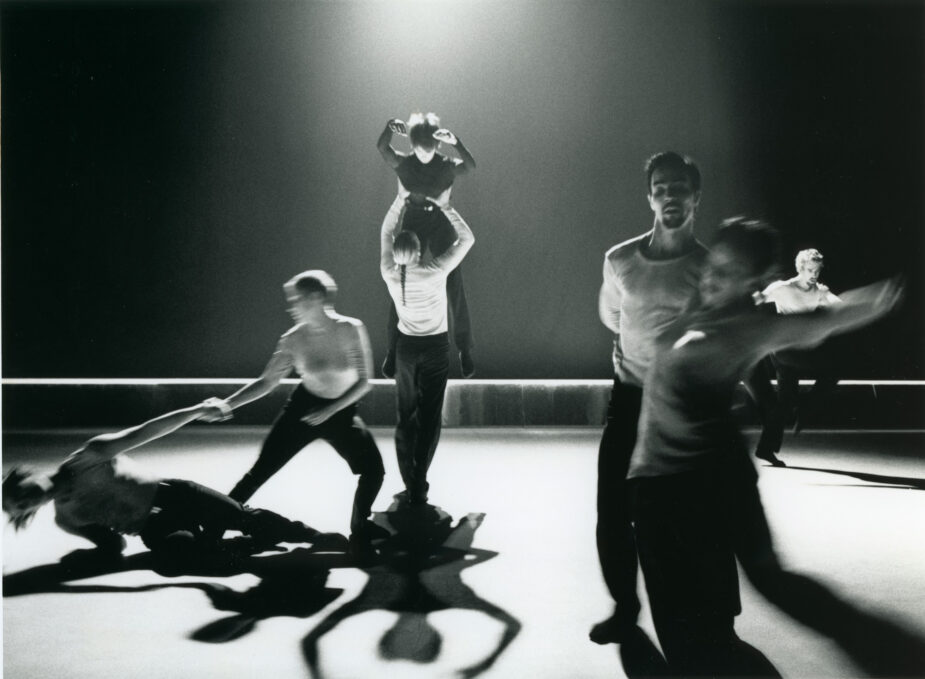

The 1990’s was marked by a fast-paced, acrobatic contemporary dance aesthetic like that seen in groups such as the Canadian company La La La Human Steps. There was a lot of movement and physical contact in the abstract works of Kenneth Kvarnström when he led the Helsinki City Theater dance company in the 1990’s. A smooth, elegant movement language combined with a stark, pure visuality spoke to young audiences in Finland and internationally. Kvarnström was later influential as director at Stockholm’s Dansens Hus and elsewhere.

The international direction of Helsinki City Theater’s dance ensemble continued when Nigel Charnock (1960–2012), a central early figure in the DV8 group in London, became the group’s director in the 2000’s. The diverse dancers in his rather uninhibited and energetic works took away a great deal from his different methods of expression.

In the 1990’s, Finnish contemporary dance gradually started to break through internationally. The breakthrough had its beginnings in the birth of higher education in dance, a broadening freelance scene, and academic models of activity and production that began in the 1980’s. Refinements of scenography that put Finland on the cutting edge were also catching on in Europe, where lighting design, for example, could still be quite traditional.

Demand and interest in Finnish contemporary dance also came by way of competitions. Susanna Leinonen‘s career, for instance, took off in the early 2000’s with her appearance at the Concours chorégraphique international de Bagnolet in France. Leinonen soon founded her own dance company and her unique, refined signature drew interest abroad.

Tero Saarinen has been among the most well-known Finnish choreographers since the 1990’s. Tero Saarinen Company’s output has from the beginning placed an emphasis on international productions on large stages and their works have broken through on several continents – in Europe, the United States, and Asia.

Influences flow in many channels

Festivals have served a significant function as meeting places for dance pieces and people. The oldest dance festival in the Nordic countries is Kuopio Dance Festival, begun in the early 1970’s. In Helsinki, the Moving in November contemporary dance festival began in 1986. Full Moon Dance Festival in Pyhäjärvi danced for the first time in 1992. Zodiak’s Sivuaskel / Side Step festival has been presenting programs on such things as postmodern dance past and present and bringing international guest artists to Finland since the late 1990’s. Zodiak collaborations with artists such as Deborah Hay have produced new solos, group works, and guest appearances.

Nowadays internationalism manifests in more multifaceted ways than it did at the beginning of the century. The field of dance is growing and changing and becoming ever more fragmentary. At the same time, the content and practice of contemporary dance is changing, too; in recent years, for instance, there have been a lot of immersive and site-specific performances. Work done in the form of international residencies interests many artists.

International activity can also be carried out digitally. Even before the pandemic, Valtteri Raekallio made digital connections when his dance films garnered a wide audience through television and film festivals. Working digitally is also a tool for reducing the carbon footprint of the dance ‘industry’ when touring.

Internationalism is not necessarily a worthy goal in and of itself. Its value lies in how international interactions can bring dancemakers new ideas and help them to encounter new and different dance techniques, collaborators, and audiences. Their own artistic identities have been clarified and international exchange at its best helps them to find their own place in the field of dance.

About the writer

Aino Kukkonen, PhD, is dance scholar and critique. This article is based on her manuscript for the Theater Museum’s Deep Movement exhibit, in 2022 in Helsinki, and it was originally published in the Finnish Dance in Focus magazine 2022.

Translation from Finnish: Lola Rogers